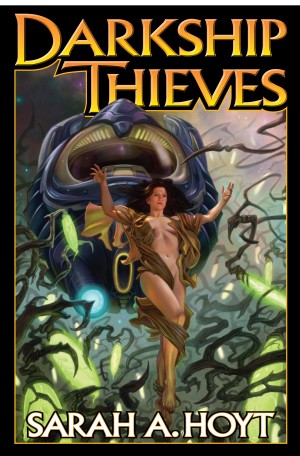

The first time I met Sarah Hoyt was in Tuscon, Arizona, at the World Fantasy Convention. I had the good fortune of sitting beside her during a little gathering set up by our agent—and oh, that was a good time. Sarah is wonderful. Not only is she a fantastic writer, she is a delight to be around, and I am thrilled that she’s my guest at the blog today. Sarah is a star with words, and Darkship Thieves is at the top of my reading pile.

***

I never wanted to go to space. Never wanted see the eerie glow of the Powerpods. Never wanted to visit Circum Terra. Never had any interest in finding out the truth about the DarkShips. You always get what you don’t ask for.

Which was why I woke up in the dark of shipnight, within the greater night of space in my father’s space cruiser.

Before full consciousness, I knew there was an intruder in my cabin.

***

Recently a review of my latest book – the Science Fiction Darkship Thieves – posited that Cordwainer Smith had been one of my great influences. While I’ve read and enjoyed Cordwainer’s work, I found him late, and don’t think I’ve read more than half of his work.

Recently a review of my latest book – the Science Fiction Darkship Thieves – posited that Cordwainer Smith had been one of my great influences. While I’ve read and enjoyed Cordwainer’s work, I found him late, and don’t think I’ve read more than half of his work.

Because the reviewer is a fan I’ve exchanged correspondence with, and because his review puzzled me, I asked him what had led him to deduce Cordwainer Smith among my influences. He said it was the sweep of history, the rise and fall of ways of life, the idea nothing was permanent.

I didn’t say anything. There are possibly some strands of Cordwainer’s DNA in the story. But more likely is that the historical feel of the book – the idea that civilizations rise, fall and leave behind the essential component parts of themselves – comes from my having grown up immersed in history.

I was born in Portugal, in a small village outside Porto, the second largest of Portuguese cities. Both in the village, where I passed most of my childhood, and the city where I attended high school in adolescence, it was impossible to avoid a sense of history. My son, when we visited this summer, told me it felt to him as though Portugal carried the ball and chain of history around its ankle and it weighed so heavily that it could not move forward.

This is a harsh way of putting it, though perhaps accurate when seen through American eyes. However, that life, mired in history, surrounded by it, constantly reminded by artifact and law and deed of the lives of those who went before us, is the normal state of humanity. America has a shorter span of history than most and it has freed her some, but America too can’t avoid accumulating a past as it grows.

And living with the feel of the depth of history in one’s immediate environment isn’t all bad. I often joke that I grew up sometime between Elizabethan and Victorian England. I found recently that the “treatment” my mom used when I had small pox (in the last great epidemic to sweep Europe in the seventies) at the age of three – surrounding me in red, from my flannel pajamas to the shade on my lamp – was the same Queen Elizabeth endured. I learned to write with a quill pen. Wind up toys were luxury.

But beyond all that, there were older, deeper reminders. In the woods where my friends and I played and explored, there were markers dating back to Roman times and the grants given to legionaires for their service. I found Latin there for the first time, and understood how the language spoken in the region had changed. Then there were the mines – from which the Romans took all the gold – stretching in all directions under the village, making the ground like Swiss cheese. My friends and I were strictly forbidden from going into them, so of course we did. (The danger of the activity didn’t really hit home, till a period of rains when I was in my twenties made the ground so soft that it caved and cars fell into the old mines.)

Then there were the tombs of the crusaders, outside the village church. One of them was on its side, the lid lost. It wasn’t until this last visit that my dad sheepishly admitted he and his friends did that, with levers, when they were in middle school. Although that prank might be a little too far, I think every generation – and mine too – got a group together in the dark of night, to shift the lid in the hopes of catching a glimpse of a skeleton. Needless to say, there was nothing but dust in there.

The village has changed a lot now and there are skyscrapers in the middle of it, mingling with the eighteenth century, the tall, stately houses and the chapel with its castle-like crenelations. Most of the people who live in the village now came from elsewhere – called by the proximity to the city and good jobs – and they have no idea of the village’s past. And yet, everyday, that past is there, by their side, in the crumbling wall around a field, in a forgotten marker in the woods, in the way people skirt around a house because once, long ago, something horrible happened in there.

And even in Darkship Thieves, where I was creating a world that hasn’t come into being yet, when my characters come on the scene it is five hundred years past our time. The intervening centuries have left marks, ruins, habits. And all of those tints blend with the newer-than-tomorrow technology to – hopefully – give the world a lived-in feeling. Like me, my work tends to be a blend of places and cultures, a painting atop of a painting. Perhaps it gives it more depth. Perhaps not. But as far as the art reflects the artist, it’s the only way I can write.

***

To read more about the novel, check out Sarah’s great post at The Big Idea, or her wonderful blog.

You can order Darkship Thieves at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Borders, and many other fine and lovely bookstores.